Every author of a musical has a project (at least one) that never finds life beyond the heart or mind’s eye. I have many. But the one that was most peculiar, now feeling more like a nutty dream, was Flying Tigers.

From 2002 to 2006 I hung up my composer chapeau from sheer fatigue. I had done similar in the late 1980s, allowing the less courageous left hemisphere of my brain to take charge. At that time I focused on new digital tech and product development at Citicorp, mentored by a brilliant boss, my own executive knight in shining armor. By 1992 I had left those cozy towering corporate offices and was happily self-employed as a tech advisor to New York theater and dance companies, agencies and unions. I had also developed a computer training curriculum (non-existent at the time) designed specifically for actors and dancers. (Yes, they are unique in how they learn.) Alongside all that, for the next ten years several musical projects bubbled and drained as my desire to conquer the Great White Way faded.

But fate indeed has a twisted sense of humor and in 2005 I received a phone call. “Roger, this is Don. Don Gregory. Remember me?”* Such moments are like running into an “ex” in the pasta aisle of the supermarket. Surprised, bewildered, yet curious. “I tried to forget you, Don, but it was a full time job, so I gave up.” Puzzled by that, he finally laughed and gave me the spiel.

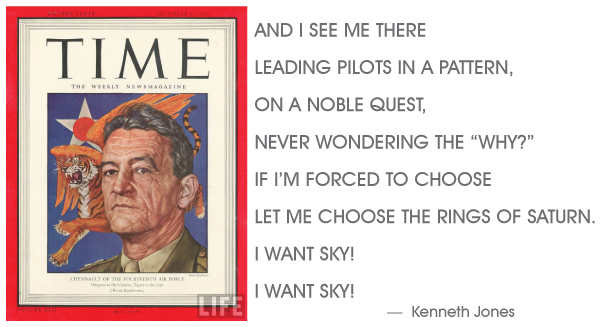

Don had been approached by Chinese investors to oversee a new theatrical musical work celebrating the Flying Tigers. These were a band of volunteer American pilots commanded by Claire Lee Chennault, a southern retired US Army aviator. The Flying Tigers’ mission was to oppose the Japanese invasion of China during the early 1940s.

William Luce, whose The Belle of Amherst Don had produced on Broadway, had agreed to write the book. Claire Chennault also grew up in Louisiana, so Don felt I was an empathetic choice as composer. Plus I had proved my ability to Broadway insiders with Shine! and Chaplin. Realizing that Lee Goldsmith was in his 80s now and not interested, a few other lyricists were suggested. But I asked he consider Kenneth Jones. Ken and I had written a few songs together and I thought it would be grand to collaborate on a full musical. Don agreed, if I could convince him Ken was right for the project.**

After several conversations with Luce and hearing his plans for the script—as well as exploring my own research into the history of the Flying Tigers, previous dramatizations and a lot of authentic Chinese music—I felt able to begin work. Even without lyrics, already my brain was spinning ideas. I knew that one central musical theme was needed to embrace the entire story. Avoiding the penta-tonic scale associated with Oriental music, I was oddly drawn more to a less authentic tetra-tonic as a simpler solution: a rotating melody to suggest the cycle of samsara, the core of Buddhism. I titled it “Heaven” after the revered 15th century temple. But of course it had to quickly become a Rodgers-like concoction. We were writing for Broadway after all, not Beijing. And so the score began to congeal in my head. I followed up with a sweeping ballad to eventually belong to the show’s love story that Luce was inventing. “This Is Where It Started, This Is Where It Ends” was my mock title. Then the massive agitated vamp to suggest the noise and ferocity of Warhawk fighters soaring above. (Don had insisted the planes would use impressive technological theatrical audio effects, but I thought a big orchestral vamp was a wise addition.) Madame Chiang Kai-shek needed a vocal showcase to her extraordinary ambition and power, so I sketched a number called “Some Men.” Our protagonist, Chennault, needed a song about missing home, haunted by the melancholy jazz tones of “Louisiana.” (Later on when Ken delivered the lyric for Chennault’s opening soliloquy, he gave me words and inspiration for the inevitable heroic anthem — “I Want Sky.”)

Meetings, emails and long phone calls continued, then an elaborate promotional trip to China for the elite members of our team (not me). Director, choreographer and designers were selected. Casting was discussed. Publicity commenced and it seemed this crazy, wild, unlikely musical was actually being born. But, of course, it wasn’t. The obtuse international fundraising and awkward management became tangled and relentless postponements followed. Eventually—poof—another musical bites the dust. Such is Broadway. I had grown accustomed to its deceptive Much Ado ways.

But, of course, it wasn’t. The obtuse international fundraising and awkward management became tangled and relentless postponements followed. Eventually—poof—another musical bites the dust. Such is Broadway. I had grown accustomed to its deceptive Much Ado ways.

Don Gregory died in 2015. In spite of my frustrating experiences with him, I remained fond of Don. After all, he believed in me, continually and against all odds. I was a risk, but he bet on me more than once. And though I did not become famous or financially enriched from any of it, he had tremendous charm and I enjoyed his company and the adventures he gave me.

After Flying Tigers was officially dead, Gregory returned to resurrecting our defunct Charlie Chaplin musical he commissioned in the early 80s, but now aimed for the West End. Sitting in a little café in London in early 2007, he quietly looked me over. “How old are you now, Roger?” “I’m 54, Don. I was 28 when we first met.” He stared at me for a while longer, smiled and said, “Wow. I’m sorry I ruined your life.” He chuckled. I didn’t.

*For background on my early history with Don Gregory, read my journal entry about the original Chaplin musical of the early 1980s here.

**To download and read Ken’s opening sequence scene which sold Don on his skill and understanding of the show, click here.